The DOE National Average is the weekly average cost of retail diesel, assessed by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). For many carriers, the price they actually pay for fuel is different than the DOE National Average. Why is this?

What is the goal of a fuel surcharge?

The basic premise of a fuel surcharge is to have the carrier set the price of fuel to the shipper on a floating basis each week. The surcharge is based on movements in the weekly price of diesel as published by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Although it comes out of the EIA, it is known in the industry as the DOE price. The primary goal of using the DOE price is to have the cost of fuel used to transport goods to be a pass-through from carrier to shipper.

How does a fuel surcharge impact gross fuel expense per mile?

Gross fuel expense per mile is the cost of fuel per mile that a fleet will pay before recouping a fuel surcharge. The formula is:

Total fuel expense divided by Total miles driven = gross fuel expense per mile

The fleet normally pays the gross fuel expense to a fuel vendor (truckstop or wholesaler) and then will recoup money from shippers in the form of a fuel surcharge. The fuel surcharge will offset a portion of the gross fuel bill. The resulting amount is known as the net fuel expense, or calculated on a per mile basis, the net fuel expense per mile.

The formula is:

Total fuel expense – fuel surcharge = net fuel expense

To calculate per mile:

Net fuel expense divided by Total miles driven = net fuel expense per mile

Where do we start in calculating a fuel surcharge?

Each Monday, the EIA releases a slew of average retail prices for gasoline and diesel. The EIA survey is conducted that day. It is not an average or a compilation of seven days’ worth of data. (If Monday is a holiday, the process is delayed by a day). There are two retail numbers that matter to the trucking industry. The first is the average national weekly retail diesel price. The second, which is far less important, is the California diesel price. It is used to set fuel surcharges in California because its prices are so far off the national averages due to its various environmental regulations. Those numbers serve as the basis for fuel surcharges.

View a primer on how diesel prices are established, prior to the setting of the DOE weekly price.

Why would this price be chosen?

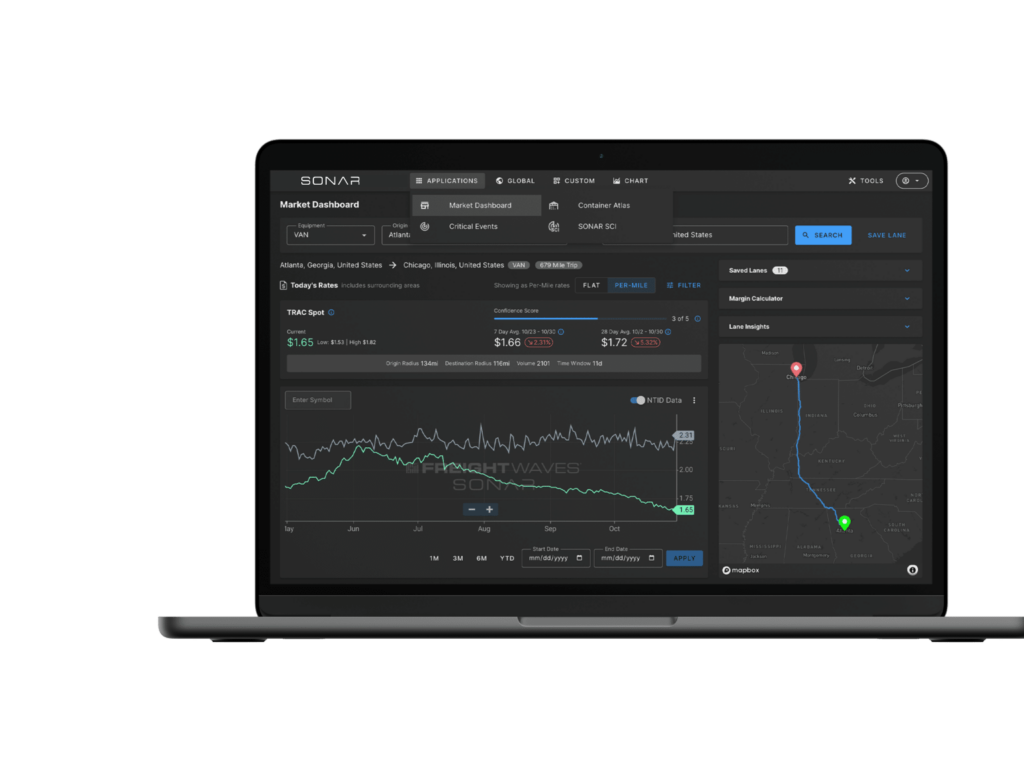

The information from the EIA has several advantages. It’s completely transparent; the information is free through the EIA website. The EIA process is detailed and subject to variability only through statistical processes. Finally, it’s an all-in price. Taxes, retail markup, etc. are all in the price. It does not need to be calculated further. While wholesale rack diesel prices are tracked with great detail each day (in SONAR they can be seen nationally at SONAR: ULSDR.USA) – use of the wholesale number would mean that there would need to be a mechanism to get that wholesale price to a retail value. That’s a lot of work and would be the basis for significant disagreement between buyer and seller.

A concept called the retail to wholesale ULSD spread is the difference between the average retail ULSD fuel prices paid at the pump and the wholesale ULSD prices paid at the rack. The ULSD retail to wholesale spread is useful in tracking the economic impact of fuel prices on trucking companies that buy their fuel at rack wholesale prices. Inside of SONAR, the spread ticker is: (SONAR:FUELS.USA). The fuel spread number does not include taxes or transportation costs to get the fuel from the wholesaler to retail location.

So I have the basis for the diesel price. Then what?

Some companies are transparent about their fuel surcharges and publish them on the internet. For example, truckload (TL) and less-than-truckload (LTL) carrier Cheeseman has a detailed page laying out its fuel surcharge. Fuel surcharges have a range of prices when it kicks in. In the case of Cheeseman, the spread is so wide – $1.14/gallon on the low, $8.70/gallon on the high – that there will always be a surcharge barring some utterly unforeseen market development.

In the case of Cheeseman, its formula works so that when the EIA posted its price of $2.507/gallon on April 14, its fuel surcharge for an LTL delivery was 13.5% of the freight charges. If it was truckload shipment, it was $0.28 per mile.

LTL carrier YRC posts its fuel surcharges as well. On April 8, when the fuel surcharge was $2.548, the YRC fuel surcharge was 21.35% against the cost of freight. For its truckload activities, it goes with a percentage, instead of the Cheeseman example that was a straight cents per mile fee. YRC’s surcharge there is 42.7%.

Charges can also fluctuate depending on the type of truck. For example, in its explanation of its fuel surcharge policies, Crete Carrier sets its fuel surcharge in part on the basis of miles per gallon. It said its trucks average 6.8 miles per gallon. That would go into the calculation of the surcharge.

Does every shipment move with a fuel surcharge?

No. According to Gregory M. Feary, a partner at Scopelitis, Garvin Light Hanson & Feary, some shippers resist them because “they don’t want to be in the fuel arbitrage business,” with the arbitrage here being the difference between what the carrier is paying at the pump and the number that sets the basis for the fuel surcharge. “They’ll say, we will consider an overall price adjustment because we understand fuel is a variable in our freight fees,” Feary explained. “But we don’t want a line item.” Their view, he added, is that it is the carrier’s job to handle the cost of fuel. “They think that the carrier is the transport company and they need to figure out what the costs are,” Feary said. “You need to figure out the variability of those costs, you charge us freight fees and we’ll compare them.”

But he added that it isn’t always accepted. “It’s counterbalanced by companies saying ‘we’re going to charge you a freight fee but there is only one variable in it.’” Carriers can not “deal with a market that goes dramatically up or down when you’re not willing to negotiate with us in that area.”

Feary conceded that from his perch at Scopelitis, he’s mostly dealing with big carriers. Given that, the big carriers have a lot more market power to enforce a fuel surcharge.

How does the EIA calculate its number?

The EIA spells out its methodology in enormous detail on its website. Here are some of the key points:

About 400 retail outlets are surveyed every Monday. There are no up-to-date numbers but the survey response percentage in 2015 was close to 99%. The gathering is done by “telephone, fax, email or the internet.”

– That group of 400 is constructed using a size-based probability to build what it considers a representative sample of what EIA says is a universe of about 62,000 retail outlets and 4,000 truck stops. Alaska and Hawaii are not surveyed.

– The inputs reflect prices on Monday. Even when there is a Monday holiday that delays publication until Tuesday, the price reflects Monday prices, not Tuesday.

The “primary publication cells” of the survey are the five Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs), along with the three subparts of the East Coast’s PADD 1 and the the subparts of the West Coasts PADD 5, which are California and the rest of the West Coast excluding California. Ironically, the number that is mostly used in the surcharge calculation is the entire U.S., which is considered a “secondary publication cell,” derived from the numbers in the primary cells.

– The numbers gathered by the survey are weighted by volumes sold among the states.

– The actual math is laid out in great detail by the EIA.

– Want to ask the EIA how to put together a fuel surcharge? Don’t bother. Here’s what it says about them: “EIA cannot tell you how to calculate a fuel surcharge. Fuel surcharges are negotiated privately by shippers and by transportation companies.”

But can a carrier make money on the fuel surcharge?

Since fuel costs that carriers are paying are subject to change every day, but the DOE price changes weekly, a rapidly falling market will inevitably have a lag that helps carriers. They will be billing a surcharge basis from a price a few days old that may not be representative of the market. That’s a potential windfall for the carriers. But conversely, a rapidly rising market means that the prices carriers pay at the pump will be rising faster than changes in the DOE price. It’s important to remember over time that price changes will generally average themselves out. For all of 2019, the average weekly change, up or down, was a slight decrease that wasn’t even one full cent. The number is larger when you throw in 2020, but that’s because of an historic market crash in the first weeks of the year.

SONAR subscribers get access to over 150,000 transportation, logistics, and diesel fuel indexes that include the DOE National Index, ULSD wholesale rack diesel prices, or the ULSD retail to wholesale spread.